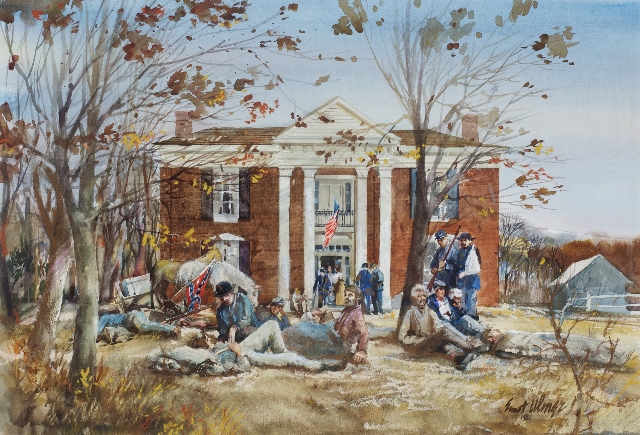

“The battlefield exhibited evidence of the fierce contest … In the field next to the lane, on this side of Wornall’s house, there were seven dead rebels lying by the side … Striking the prairie beyond Wornall’s the evidences of the fight were visible all about – dead horses, saddles, blankets, broken guns and dead rebels.”

— Kansas City Journal of Commerce describing the aftermath of the Battle of Westport, October 24, 1864

The Border Wars

Following the Kansas-Nebraska Act, immigrants supporting both pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions streamed into Kansas Territory, intending to influence the vote, sometimes fraudulently. These included pro-slavery men known as “Border Ruffians” and abolitionists known as “Free Staters” or “Free Soilers”. Violence in Kansas Territory raged in the lead-up to the Civil War as tensions continued to mount and skirmishes took place between various factions. These included the Sacking of Lawrence, the Pottawatomie Massacre, the Battle of Osawatomie, and the Marais de Cygnes Massacre.

The Wornall family remained relatively untouched by Border War violence, but were certainly aware of the potential danger. The Civil War finally erupted in 1861 when secessionist forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina. For Missourians and Kansans, this was simply a continuation of the violence they had already experienced.

It is unclear exactly how John Wornall felt about the Civil War – he was a slave owner with Southern sympathies but maintained neutrality throughout the conflict.

1862

Frank’s Dare

As a dare from a servant girl named Mittie Pigg, John’s oldest son Frank yelled, “Hurrah for Jeff Davis!” at some passing Union troops. (Jefferson Davis was president of the Confederate States.) As a result, his father was captured by Union soldiers and was to be killed under suspicion of Southern loyalty. Luckily for the family, Eliza Wornall was able to explain Frank’s childish behavior and John was released.

1863

Occupation and Order No. 11

In early 1863, Colonel Charles “Doc” Jennison, leader of the Seventh Kansas Calvary, commandeered the Wornall home as his headquarters. About 200 men occupied the farm for eight days, burning fences, killing livestock, and destroying crops. At the end of the eight days, Jennison admitted he had come to kill John because of his southern sympathies, but left peacefully, impressed by the hospitality he received. He paid $2,800 to John for damages done to the farm.

In August 1863, the Union Army attempted to establish control by issuing Order No. 11. This order gave residents, regardless of loyalty, living in several Missouri counties 15 days to evacuate their homes. The intention was to cut off support for southern-aligned Bushwhackers. John Wornall signed a loyalty oath and purchased a home in downtown Kansas City to escape the violence. Many homes were burned to the ground after the order, but the Wornall House was luckily untouched, although it was looted. The Wornalls returned to their home sometime in late 1863/early 1864.

1864

Robberies and the Battle of Westport

Despite being known for having some amount of Southern allegiance, John was robbed and threatened by Bushwhackers at least twice in 1864. On one occasion, John was almost hung from his own balcony by Bushwhackers in a botched robbery attempt. On another, the the Kansas City Journal of Commerce reported, “We learn that a gang of bushwhackers robbed Mr. Wornall about four miles from Westport, being close to the state line, night before last. They took his watch, money, and all his clothing, even to the coat on his back and his underclothing; also two horses. There were eight in the gang.”

The culmination of this violence was the Battle of Westport on October 24, 1864. The heaviest fighting took place at modern-day Loose Park, one mile north of the Wornall House. Each side suffered approximately 1,500 casualties and makeshift hospitals were set up, including in the Wornall House. Confederate soldiers commandeered the house in the morning, destroying most of the furnishings. As the Confederates retreated, all their wounded who could be moved were taken away, and then the Union army used the house for their injured.

“In a few hours the house was full of the wounded and dying.” – Frank Wornall

1865

Fleeing the Wornall House

On January 5, 1865, the Wornall family attended the funeral of Eliza’s father Thomas Johnson. Johnson was killed by Bushwhackers, possibly because of his perceived betrayal of the Southern cause. Johnson was a slaveowner and politically supportive of the pro-slavery cause for many years before eventually declaring his support of the Union in the early years of the war. On their way back from the funeral, the family received a letter warning them not to return to the Wornall House “without sufficient protection” under threat of death.

The family fled to the safety of their downtown Kansas City home. Although the war ended in April 1865, they did not return to the Wornall House until 1874.