The Wornalls, like many settlers from the upper South, brought the culture of slave ownership with them when the migrated from Kentucky to Missouri in 1843. Slavery was already well-established in Jackson County, Missouri when they arrived – at the time, enslaved people made up about 15% of the population of the state. Missouri was what was known as a “small scale slaveholding state” – most slaveholders had 10 or fewer enslaved people. Even for those who did not own slaves, slavery was a part of every day life.

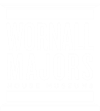

Richard Wornall (John’s father) owned six slaves in 1850 on the Wornall property: five young men between 16-24 years old and a 35-year-old woman. Eventually, John became the owner of those six people when his father returned to Kentucky. By 1860, there were four enslaved people on the property: two adult women, a young man, and a female child.

The 1850 Slave Schedule, part of the 1850 United States Census, showing Richard (Rich) Wornall’s slave holdings. Unfortunately, you can see that the enslaved are identified only by age, sex, and race, but not their names.

An enslaved family in Hanover County, Virginia, 1862. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Work of the Enslaved

The wealth and prosperity of the Wornall family would not have been possible without the work of the enslaved.

The Wornall family left behind much documentation about the hired white builders who oversaw construction and carpentry at the Wornall House. There is no mention of who performed the physical labor of construction. It is likely that much of the work was done by slaves. Brick for the Wornall House was fired on site – an extremely labor-intensive job. John may have hired enslaved bricklayers to build his home. Many slaves were trained in highly valuable trades like bricklaying and blacksmithing. These individuals were then “hired out” by their owners for fixed periods of time or for specific projects.

In addition, the enslaved would have been involved of all aspects of life on the farm. They would have planted, tended, and harvested crops, reared the Wornall children, cooked, cleaned, and run errands in addition to maintaining their own lives and households.

Naming the Enslaved

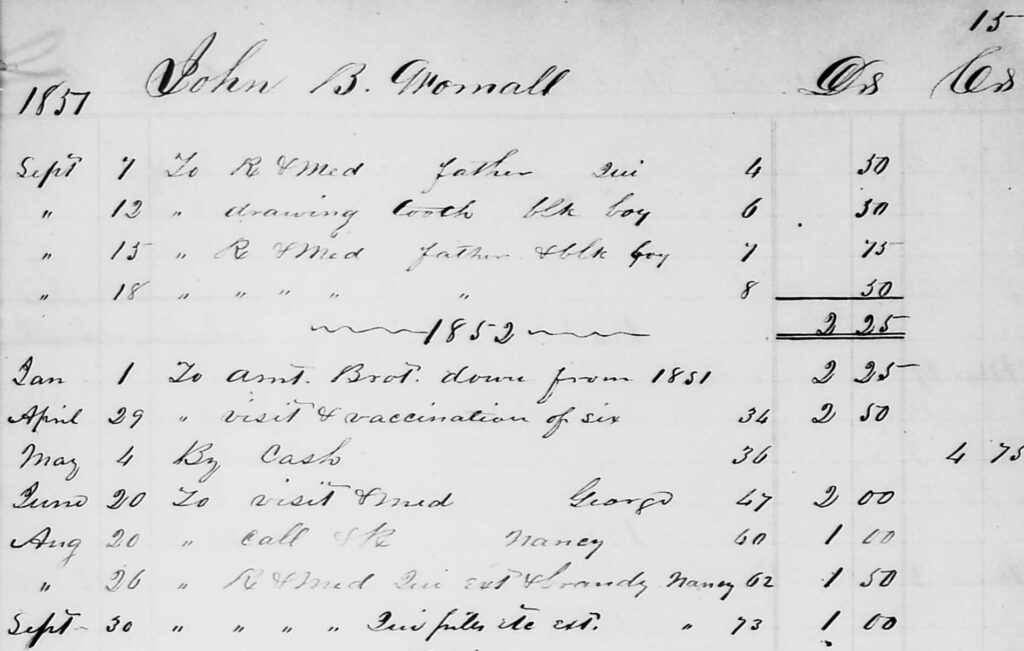

The individual identities of those enslaved at the Wornall House have long been unknown. Any record of their names has been lost or never existed. However, when researching Wornall family medical receipts, museum staff came across four unfamiliar names: George, Allen, Jim, and Nancy. Who were these individuals? They were not the names of any family members, field hands, or known associates. Whose medical care would John Wornall have paid for, if not family members or employees? We have concluded that George, Allen, Jim, and Nancy were most likely enslaved, finally giving names to some of those enslaved here.

Learn More

The Wornall House has recently added signage about slavery at the Wornall House, using primary sources related to the Wornall family, the Missouri slave-owning community, and the enslaved in Missouri and across the United States. George, Allen, Jim, Nancy, and the others enslaved at the Wornall House were just as present at the home as the Wornall family, and despite a lack of information about their individual lives, we hope to honor their existence by providing as much comprehensive information as possible to explore what their lives may have been like.

Enslaved vs. Slave – What’s the Difference?

You may notice that we tend to use terms like “enslaved man” or “enslaved individuals” instead of “slave.” This is intended to give each individual humanity versus making their identity contingent on an act imposed upon them. Many scholars and historians have moved toward using this language, but it is not universally agreed upon. We try to use the most accurate language possible without confusing our readers and visitors, and you may see both instances used, although we prefer to use “enslaved” when possible.